What is the value of accuracy?

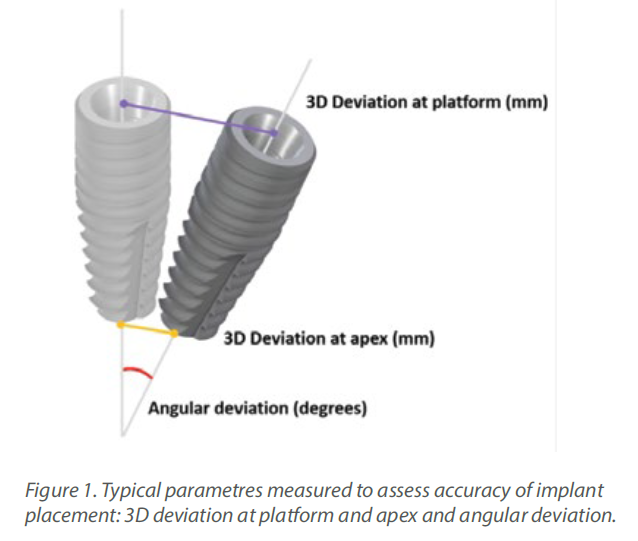

Accurate implant placement was the primary and most important advantage reported for CAIS. To measure the extent of this accuracy, researchers have used the 3-dimensional deviation from the planned position at the

Accurate implant placement was the primary and most important advantage reported for CAIS. To measure the extent of this accuracy, researchers have used the 3-dimensional deviation from the planned position at the

implant platform and apex and the deviation in the angle (Figure 1). Initial research pointed out to a significant increase in accuracy when CAIS

was used, with the deviation reduced to roughly half of what it was in freehand implant placement. An earlier systematic review from the ITI Consensus Workshop of 2017, found that static CAIS would result to deviation of 1.2mm at

implant platform on average (1), suggesting that a safety margin of 2mm is to be considered when we use this technology. Although certainly a great development, is this something that could transform your practice? Many

colleagues remained skeptical, especially those with long experience. After all, gadgets are always cool, but we’ve been placing implants with great success already. Is it worth all additional investment and effort?

Shifting Paradigms – Shifting Needs

Before we start discussing about accuracy there is one important question each should ask oneself: “how critical is to achieve precisely my planned position?” The answer might be different for each patient case and was different through the different ages in the evolution of implant dentistry. In the earlier decades of implant dentistry, when the dominant paradigm was the seek for osseointegration, the placement was driven by the anatomy. Exposing an edentulous jaw, the surgeon would determine the final position based on his assessment of the sites that could offer best conditions for osseointegration. Then, several months later someone would come and join all the implants - wherever placed - under one full-arch reconstruction. As you can understand, reconstructions varied significantly, the plan was only approximate – at least by today’s standards - deviations of implant position could extend to centimetres, while even the number of implants could change intraoperatively. Once replacement of single units became established, the margin of acceptable deviation was narrowed, and the implant placement became increasingly driven by the prosthetic needs. The development however of more sophisticated prosthodontics, (abutment dimensions and angles, retention methods) allowed

still a significant “leeway” for implant positioning. Today, implant dentistry has completely departed from the older paradigm. Modern surfaces and implant design, as well as bone regeneration techniques have made osteointegration to be no longer the key determinant. The guiding paradigm today in implant

dentistry is this of designing a new organ, which will serve function and aesthetics but also where mechanical components, human tissue and bacteria

can reach a long term balance of health (2). This requires a lot of attention to be given to the proper design of the prosthesis, the shape and morphology of

the Implant Supracrestal Complex and finally defining the single optimal implant position and type. Even more, the rising concept of immediacy, with an immediate temporary or loaded prosthesis adds critical importance to the implant position. Even a small deviation from the planned position can be detrimental to immediate loading when a pre-fabricated prosthesis is used. So ask yourself, how important is it to reach the planned position with high accuracy? If you perceive the implant-prosthesis complex as one system in close interrelation with the tissue, the answer is that implant position is always critical. Today, we always need to have defined the optimal implant position. The tolerance for deviation and consequently the need for accuracy might differ, depending on the site and the treatment plan. In the case of a single posterior implant to be restored conventionally, we might be able to get away with some significant deviation through “damage-control” prosthodontics. On the other

extreme, in an anterior aesthetic case or a full arch planned for immediate restoration, even a small deviation would jeopardise the whole plan. And yes,

1 mm can be the game changer indeed in many cases.

CAIS Technology

The CAIS tree started initially with two main approaches, the “static” or “guided” and the “dynamic” or “real time navigation”. As with everything new, the terminology is a bit confusing at times, in particular in studies comparing CAIS with conventional placement. So in some studies you will see the conventional placement to be reported as “freehand”, but that will be misleading as the placement with real time navigation is also “freehand”. In other studies the conventional placement was referred to as “mental” guided, but that is misleading too, as mental capacity should be behind any kind of placement. On top of that, with the meaning of “mental” in colloquial American English and with the mental pressure we have all been subjected to under the years of Covid-19, this term is not particularly attractive. So, to streamline our terms a bit, CAIS implies the use of digital aids or products during the surgical implant placement. It can be static, where the surgeon places the implant in a pre-determined position by means of a surgical guide, or it can be dynamic, (which is actually freehand), where the surgeon places the implant by means of real time projection of the osteotomy on a screen, in relation to a pre-identified position. These two technological principles have now evolved and diversified so much, that we can describe a whole “technology tree” with many branches already.

The Static CAIS Technology

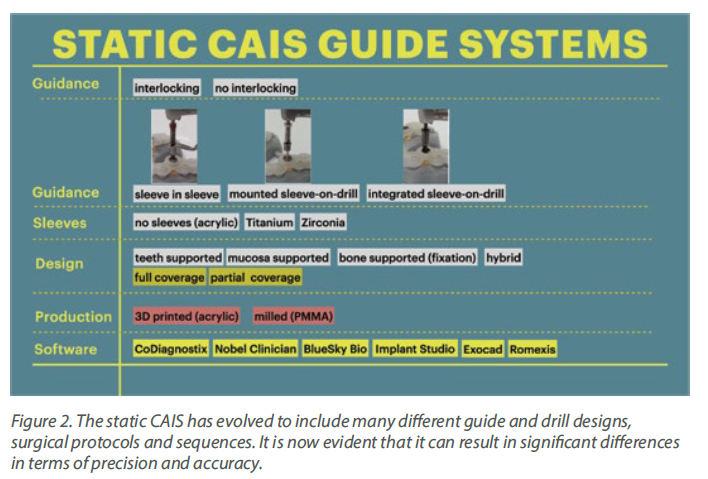

The main idea behind the static CAIS is rather simple: create an acrylic “template”, which will guide our drills to the perfect osteotomy and then place the implant accordingly. It is based therefore on a 3D printed surgical guide with “sleeves”, which allow the placement of the drills controlling angle and position

and “stops” to control the depth. The guide can be supported on teeth, on oral mucosa, on the underlying bone through mini screws or a combination of the previous. It can be a single piece guide, or “stackable” in order to cover several procedures, such as for example a possible ostectomy prior to implant placement or a lateral sinus floor augmentation. But this is about where the principle ends and the application starts! Today almost every major implant brand has its own guided surgery software, instruments and overall protocol (Figure 2).

The differences can be significant and this diversity is not based on evidence, but rather reflects each company’s philosophy, design, historical features and insider-view on implant surgery. Does it really matter? Well, evidence shows that it does. In a recent study we compared the precision of implant placement with 5 different commonly available guide designs and guided surgery configurations (3). The results showed significant differences, with the “sleeve in sleeve” guides achieving almost half the deviation than some of the “mounted” or “integrated” sleeve guides (Figure 2). At the same time, accuracy might be

not the only parametre that is clinically important in a system. Ease of use by the surgeon, reliability of the full workflow, availability of a wide array of drills, sizes and components, durability and costs are also to be accounted for. As we begin to understand the implication of design parametres through proper research, guided surgery kits in the future might start to converge towards the best practices or principles which deliver the most. For now however, be mindful, there is not one such think as “static guided surgery protocol”, despite what some systematic reviews will try to convince you. On the contrary, there are many different protocols, with significant differences in results, potential and limitations. Choose wisely!

The Dynamic CAIS Technology

The dynamic CAIS systems are based on a principle which reminds the GPS navigation. In the first generation systems, a set of stereoscopic cameras was constantly recording the position of a set of trackers (called fiducial markers) on the patient and the surgeons handpiece. The software then calculated the exact location of the patient and the handpiece in space and projected the drills on the actual patient’s CBCT in real time, through a screen (Figure 3). Of course, this only made sense if the software could maintain at all times a proper spatial alignment of the patient and the drills. To achieve this, the patient had to wear

a custom-made split during the CBCT and during surgery, but also sensitive registration and calibration procedures were required before the surgery. The first and second generation of dynamic systems utilised many components and required rather big areas of fiducial markers (Figure 3). Like in static CAIS also here, there is not a uniform technology and many companies have developed different systems. In this way, there has been systems with 2, 3 or 4 tracking cameras, different size and design of fiducial markers and calibration procedures, as well as different planning and visualization software. There is very little reported in research with regards to comparisons on different dynamic CAIS systems, so one can only try to assess systems performance based on their reported specifications.

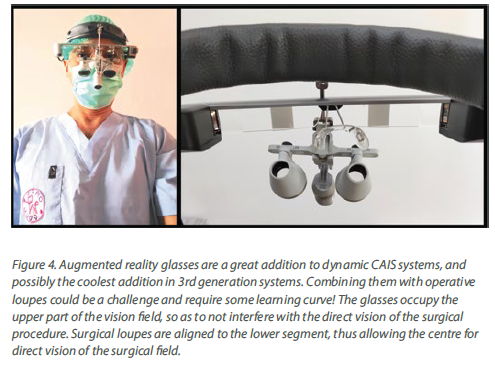

The third generation of navigation systems has reduced the need of an intraoperative splint for the patient and instead aligns the surgical visualization via an algorithm directly with the CBCT, using distinct anatomical landmarks on teeth. In general, the trend has been to reduce the number of components as well as streamline the design to smaller and easier to use. One of the latest developments is the addition of augmented reality glasses, which has made the need for chairside operating monitor redundant. This is a major improvement for both speed and ergonomics, as the surgeon has now the navigation screen projected in the upper segment of his view and can perform the surgery without

interrupting optical contact with the surgical field. Combining the augmented reality glasses however with surgical loops and light might be a challenge. Learning to operate with all these gadgets mounted and a 3-layer field of vision would require some learning and adaptation (Figure 4).

Precision and Accuracy

As the CAIS systems were initially produced to help clinicians

transfer the planned implant position in the mouth, it is not

surprising that the first objective of research was to test them

for Precision and Accuracy. In daily communication these

two terms are often used interchangeably, but when it comes

to scientific use, they imply two different qualities (Figure 5).

Accuracy will assess how close your placement will be to

your planned optimal position. Precision on the other hand

will assess how reproducible is the process, that means if you

repeat the same placement many times, how close will each

placement be to the previous ones. In practical terms low

precision but high accuracy will reveal some systemic error,

for example some error in calibration resulting in the

misplacement of the drill position in the software projection.

This misplacement will be the same for every drill, resulting in

This misplacement will be the same for every drill, resulting in

a corresponding misplacement of the implant.

To test accuracy, we would typically rely on clinical studies,

which are the most relevant. However, as in clinical studies

we can only place each implant once, to assess precision we

would need simulation studies (3), where the implant is

placed in multiple identical models under the same

conditions and by the same operator.

Before we estimate the accuracy of CAIS however, we will

Before we estimate the accuracy of CAIS however, we will

need to note that the actual guided surgery is only one final

step of a long sequence in a digital workflow. This workflow

includes a lot of steps, each of them with potential for errors.

First, we rely on a CBCT. Unlike what you might think, the 3D

image of the CBCT software we work with in our computer

screens is not a radiographic image. It is an algorithmic

reconstruction of many radiographic images. A periapical

radiograph taken with the parallel cone is a true radiograph,

as the beam of rays is what actually “writes” on the

radiosensitive plate. Any distortion in size is directed by the

laws of physics. In the case of a CBCT however, a large

number of radiographs is “sutured” together in a seemingly

3D structure by a mathematical algorithm. Every algorithm

will use at certain points some “imagination” to fill in the gaps

between the radiographs, a process which is a calculated

“approximation” and might not always be absolutely loyal to

the true anatomy. Adding to that some well-known

limitations due to position of the beam, rotation, distances

from the source of the rays and more, one can easily

understand that although a CBCT is a highly accurate

reconstruction for measurements, there is an inevitable error

reconstruction for measurements, there is an inevitable error

which might differ from machine to machine, day to day and

even patient to patient. Some studies have found that linear

measurements on well calibrated CBCT can have as much as

0.6mm inaccuracy from the true anatomy (4), while

volumetric measurements can deviate as much as 4.4% (5).

Importing the DICOM file to the treatment planning software

invites one more algorithm in the party. Then transposing the

STL file from the optical scan and the essential rendering has

the potential to further influence dimensions. Finally, 3D

printing of a surgical guide is a workflow step with potential to

introduce some more distortion.

Conclusively, by the time we are about to use our CAIS

system to place the implant, there is already some

accumulated error from the workflow, that even if the CAIS

was to be perfect, we would still observe some deviation from

the planned position. How much of the deviation is attributed

to the actual CAIS and how much to each of the previous

workflow steps is next to impossible to find, especially

considering that each software algorithm is a “black box” for

us clinicians and researchers. We just have to bear in mind

that every time we compare two CAIS systems, we do not

compare just two drilling protocols. We essentially compare

two complete workflows, including the respective software

and all algorithms used. At the same time, it becomes

apparent that comparing accuracy estimates between

different CAIS systems is meaningful when the workflow is

identical, which includes the CBCT and planning software, as

well as the operators and clinical setup.

Accuracy of CAIS Systems

Back to the main point now: how accurate is implant placement when we use CAIS?

To answer this allow me to discuss the results we have

Back to the main point now: how accurate is implant placement when we use CAIS?

To answer this allow me to discuss the results we have

accumulated through a major CAIS research project in our

clinic at Chulalongkorn University in the past 3 years (3,6-11).

This project has by now involved more than 200 patients and

included research protocols in many different clinical

scenaria. The strength of this project is that it allows us to

shape a comprehensive view of the effectiveness of CAIS,

while limiting as much as possible the variation of the

workflow error. A typical systematic review will compile

numbers from many published studies, e.g. 2 studies from

centre A on single gaps and 1 study from centres B and C

each on fully edentulous patients. It would be very difficult to

draw any valid conclusions on the accuracy of CAIS in single

gaps as opposed to fully edentulous, because the 3 studies

essentially report the results of 3 different workflows. The

three centres use a different CBCT machine, a different

planning software and in the case of static CAIS they might

be using different printers and guided surgery implant

systems. With all these different parametres contributing

differently to the potential errors, it is impossible to conclude

what is the impact of the clinical condition (single gap vs fully

what is the impact of the clinical condition (single gap vs fully

edentulous) in the finally reported accuracy numbers.

By standardizing the studies however and using the same

technology and software, the same operators , clinic set up,

as well as the same patient pool like we have done in this

project, we can at least ensure that the workflow error is

similar in all cases thus the observed differences can be

attributed to the clinical conditions we investigate.

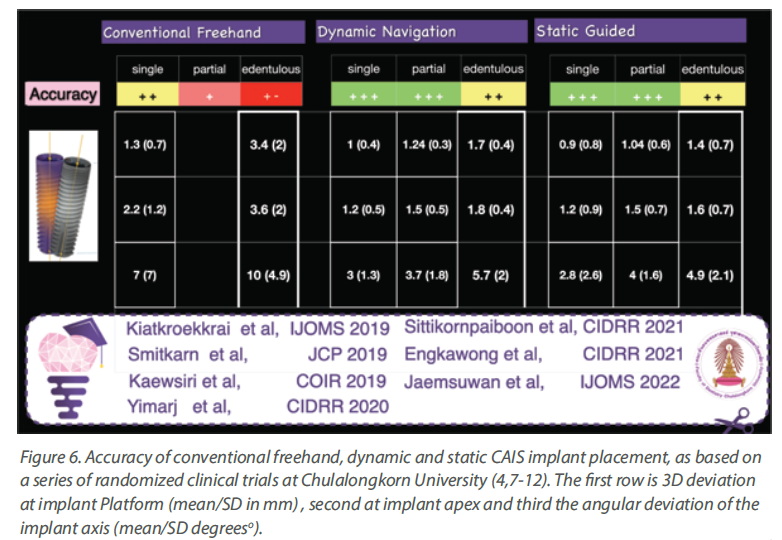

And at last, time to talk some numbers, which you can see in

Figure 6. The table is compiled out of a series of published

studies in our centre, where all cases were treated by the

same team, using the same CBCT machine as well as

planning software and implant system. Streamlining the

workflow, one can now see a clear trend with the accuracy of

CAIS being closer to freehand at single gaps, while the

deviation drastically increases as we move to partially and

fully edentulous patients. The deviation also trends to be

slightly higher in dynamic than static guided when we are

dealing with partially and fully edentulous cases, but at the

same time both static and dynamic CAIS perform

increasingly (and significantly) better than freehand

placement, as complexity increases.

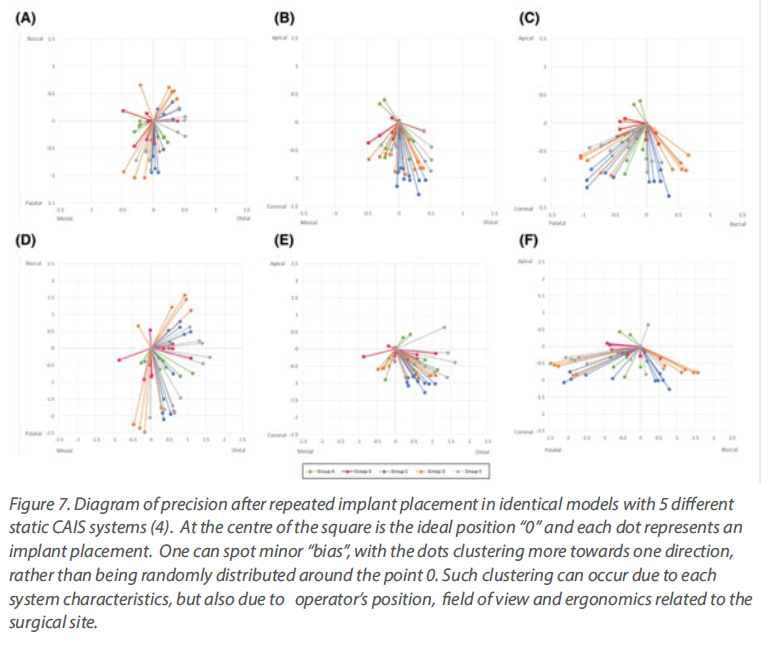

With regards to precision now, one would have to

With regards to precision now, one would have to

utilize simulation studies analysing the

distribution of the deviations in repeated implant

placement using the same workflow as we used in

the clinical studies above. The results both for

static and dynamic CAIS speak of high precision

with little indication of any systemic deviation,

other than possibly a minor influence of

ergonomics and the optical field of the operator

for some specific anatomic locations, which might

be patient specific and vary between static and

dynamic CAIS (Figure 9) .

Nevertheless, although precision and accuracy

Nevertheless, although precision and accuracy

remain the first and primary research focus, they

are just the “tip of the Iceberg” when it comes to

utilizing CAIS. Other clinical outcomes are also

very important such as implant stability,

complication rates, invasiveness. Decision

making also relies on the overall efficiency of each

method, cost/effectiveness, time allocation, initial

investment and not to forget the importance of

the patients’ own experience, understanding and

perceptions. The picture is also completed by

anatomic conditions and the treatment

objectives, which might also play a critical role in

determining the technology that works best in

each case. Finally, combining all these factors we

can produce a decision-making tree helping us to

assess the individual patient and select the most

appropriate CAIS protocol where it offers the

greatest advantage. But if you are interested to

hear more on all these, we will have to return with

a second article in a future issue!