The journey of the implant patient is a long one, as it usually starts long before we meet them for an assessment or implant consultation. For many of them started long time before, diagnosed with periodontitis, then continued with different stages of treatment with active interventions possibly interchanged with phases of maintenance therapy, with a final stage of loosing one or more teeth. For others it might have been a shorter journey, having received a late diagnosis of advanced conditions that warrants implant placemnent, while others might reach us after a long period with missing teeth, having recently for some reason opted for a replacement. In any case, implant rehabilitation aims to restore function and aesthetics, but also support all psychosocial aspects of a healthy and stable dentition. But as every patient’s journey is different, everyone will come to your chair with different luggage and putting these luggage through your x-rays might be as important as the actual oral radiographs for a successful treatment planning. The patients behavioural background, including their self-perceived condition and needs, their expectations and understanding of implant therapy could significantly influence their perception of the treatment outcome and consequently the success of the implant therapy. Recently, certain psychological disorders have also been shown to pose great risks for implant therapy. Finally, the patients’ journey might be further perplexed by a diagnosis of peri-implantitis, which could come with significant behavioural implications, while its management would require the full patient engagement and participation. The dentist is not a psychologist; yet so much of our treatment success depends also on behavioural understanding and intervention, that we cannot afford to miss out. Luckily a whole new direction of research has been developed to help us out, involving a wide array of studies under the name Patient Reported Outcomes/Experience (PROs/PRE).

Assessing patient reported outcomes / experience - concepts and instruments

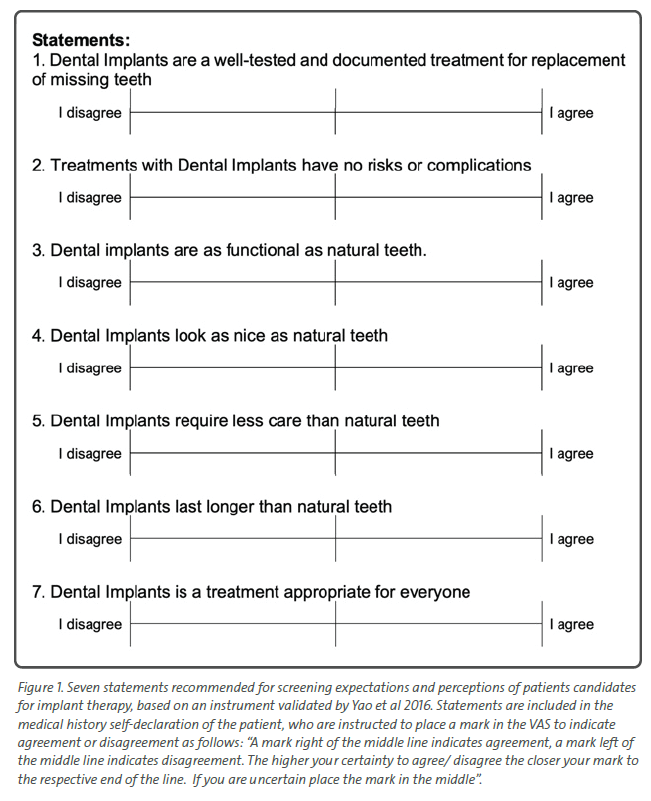

Understanding patients’ perceptions, values and viewpoints is one of the three essential components of evidence-based medicine (Sackett et al, 1996) and is acritical parametre for assessing treatment needs, planning suitable therapies, and ultimately, reaching a positive clinical result. The concept of Oral Health-Related Quality of Life (OHRQoL) was developed to evaluate the impact of oral disease, as experienced by the patient. Thereafter, several instruments have been developed to assess the impact of disease or treatment interventions on patients’ satisfaction, experience and self-perceived quality of life. Despite its documented value, as well as increased popularity in research, instruments to record PROs and PRE have been almost exclusively developed for clinical trials with large number of patients. The use of such instruments however outside research settings, e.g. with individual patients in day-to-day care might be of little benefit or relevance. Simple statements formed as “agree-disagree” visual analogue scales have been proposed by some authors as means to “screen” patients with misperceptions, but even in such cases the appropriate remediation follows with different forms of personal communication (Figure 1).

How to assess patients’ behavioural background before implant placement?

Key self-reported parameters which have been shown to potentially influence treatment success include expectations, perceptions (Yao et al 2014, Sermsiripoca et al 2021), attitudes (Yao et al 2017, Korfage et al, 2018), anxiety (Abrahamsson et al, 2017), and personality traits (Abu Hantash et al, 2006). Among the five dimensions of personality (neuroticism, extraversion, openness, agreeableness, and conscientiousness), neuroticism was the trait reversely associated with overall satisfaction after implant treatment.

Despite the increasing emphasis on the role of expectations and perceptions as part of assessing the candidate for implant therapy (Yao et al 2014), measures related to patient-reported expectations have been little studied and scarcely reported. A frequently overlooked but important starting point to understand a patient’s expectations and gradually build the appropriate communication strategy is the patients’ chief complaint. Patients who include implant-related expectations in their chief complaint, might present a clearer goal and tend to be more prepared for discussion about the treatment.

Yao et al 2017, Sermsiripoca et al 2021 and Vipattanaporn et al 2019 developed and utilized questionnaires to assess patients’ expectations and perceptions. Although these instruments were of different levels of complexity reflecting the needs of research, the authors suggested that simplified segments of the questionnaires were well suited to serve day-to-day practice as well. This consisted of simple statements to which the patient was invited to agree or disagree with, also registering the extent of agreement/disagreement on a VAS (Figure 1). By recording the patients’ extent of agreement/disagreement of such statements during the medical history documentation, researchers reported they were able to “flag” patients with misperceptions and over expectations and consequently attempt to manage them accordingly with remedial discussion. From the same studies emerged that more than 30% of the sample appeared to maintain dangerous misperceptions typically overestimating dental implants longevity and underestimating risks and the need for maintenance care (Yao et al 2017), while some of the misperceptions were found to be maintained even after the completion of the treatment (Sermsiripoca et al 2021). This might be not surprising given the fact that clinicians have been shown to be sometimes reluctant to voluntarily offer information about the longevity/ lifespan of dental implants and might have different opinions regarding the timing of information related long-term maintenance needs (Kashbour et al 2018).

Special considerations for patients with behavioral disorders

Implant therapy becomes increasingly complicated if the patient is under certain behavioural disorders that might influence his ability to understand the treatment implications and thus to offer informed consent. One such disorder which even more is likely to reach the dentist undiagnosed is the Body Dysmorphic Disorder (BDD), which evolves from preoccupation with an imagined defect or flaw in physical appearance that cannot be observed or appears slight to others. It is often referred to as disease of “imagined body ugliness" and is reported prevalence is between 1.7 – 2.4% of the population globally (Al Shuhayb et al 2023) but can rise up to 32.7% among patients seeking cosmetic surgical procedures (Nabavizadeh et al 2023). BDD can be a serious

long-term disorder and has significant comorbidities such as depression, obsessive compulsive disorder and suicidality. Teeth and smile are the 3rd most common body part that BDD patients focus on, after nose and skin. Thus, the dentist is a frequent first recipient of such patients (James et al 2019), especially if perceived to specialise or offer invasive cosmetic procedures such as correction of “gummy” smile or similar . Such patients will not show direct signs of cognitive or behavioural impairment, with the only warning sign at times being a seemingly excessive preoccupation with specific aesthetic features. Being aware of BDD is the first critical step for a dentist to recognize or suspect such condition in their patients. Asking simple open-ended questions might be helpful, such as “how much time do you spend worrying about your appearance?” As rough approximation about half of BDD patient spend on average 3 hours per day ruminating about looks (Bjornsson et al, 2010), and many patients spend most of their waking time doing this. It is highly advisable to not proceed with periodontal plastic or implant surgery in patients suspected of having BDD without ensuring professional psychological assessment and, if needed, support.

How aware are peri-implantitis patients of their condition?

Patients’ awareness of peri-implantitis is limited. Cross sectional studies have shown inability of patients to differentiate at large between healthy implants and those affected by peri-implantitis, even when they can see the respective implants in the mirror (Romandini & Lima 2021). When it comes to biological and technical complications it has been shown that the ones impacting patients’ quality of life are the complications affecting chewing ability (Esteve-Pardo et al 2023). It appears that for many of the implant patients, the first time they hear of peri-implantitis is when they get diagnosed with it, a situation which sometimes leads to a deleterious cascade of emotional reactions, resulting in disappointment, resentment, and loss of trust to the therapy and the caregivers (Abrahamsson et al 2017).

How to best remediate for patient’s misunderstandings and misconceptions about implant therapy?

“What you say before treatment is an explanation, what you say after is an excuse”, a statement that is particularly true when it comes to dealing with implant patients. At a diagnostic stage we have to assess patients’ expectations and perceptions as part of our standard clinical assessment and if unrealistic expectations or misperceptions are idenfied, to remediate accordingly. In most cases this implies proper patient education. Patients’ education has been attempted in many ways and with different levels of success, from books, notes, resources and phone apps to multimedia and websites. Nevertheless, the

face-to-face patient to doctor open ended communication, remains an essential part of diagnostic and therapeutic practice and still, probably the most effective way to comprehensively assess PROs and PREs in day-to-day clinical care settings. Taking time to listen to what patients have to say and asking questions with focus on emotional issues, establishing rapport and building a “therapeutic alliance” remains invaluable in understanding the individual patient and its perspective in day-to-day practice.

Conclusions

Instruments assessing PROs and PREs are increasingly valuable to document the impact of implant treatment on patients’ quality of life, but also to offer a deeper insight to the clinician of important behavioural patient traits and perceptions. Patients’ expectations and perceptions can interfere with the treatment success, both as it is defined by the clinician as well as the patients’ own perceived success and satisfaction. Unrealistic expectations, lack of comprehensive awareness of maintenance needs, limitations and risks is a major threat to the long-term success of implant therapy, thus a behavioural assessment is essential part of diagnosis and treatment planning procedures of the patient candidate for implant therapy. Despite its potentially detrimental effects, patients are largely unaware of peri-implantitis because most cases present asymptomatically.

Thus, it is not uncommon that many patients find out the problems related to peri-implantitis only after they are diagnosed with it, leading to feelings of disappointment and loss of trust to the treatment and the care givers. The clinicians will have to commit to significant effort to establish a “therapeutic alliance” with such patients and successfully lead the treatment processes with them as a shared responsibility.

Experimenting with Patients’ Education Booklets

Having experimented for a decade with patients’ education in the Implant Dentistry programme, we started with a 56 pages patient book compiled by a major international implant association. The patient education booklet included 56 questions and answers, but we soon found out that most patients, although welcomed the booklet did not appear to actually read all this information. We then decided to develop our own booklet a much shorter one with only 12 questions/answers based on the most common misconceptions our patients had presented with (Figure 2, 2a,b,c). We further made this booklet available in English and traditional/simplified Chinese. We found that the short booklet was much more effective than the lengthy ones. The same booklet was then translated in Thai language and used at Chulalongkorn University in Bangkok, where we received the feedback that the patients did not seem able or eager to relate to some of the clinical images. In response, we removed all clinical images/ radiographs and replaced them with artistic representations aiming to foster an emotional response rather than focus on graphic details of the anatomy and the treatment. The upgraded booklet with the artistic representations proved to be a hit wit the patients (Figure 3, 3a,b,c). In the end however it was clear that no matter how well designed or popular booklets have certain limitations. Patients often perceive the information in such booklets as “generic” and fail to see how it relates to their own, specific situation. Consequently they tend to miss important aspects, even after having read the provided booklets. Such “pre-compiled” information is important to set the stage and prepare the patients understanding, but the need remains for individualised, face-to-face, in depth discussion. Taking time to listen to what patients have to say and asking questions with focus on emotional issues, establishing rapport and building a “therapeutic alliance” remains invaluable in understanding the individual patient and preparing them for a successful and long lasting implant treatment.